Combining Like Terms

“All human wisdom is contained in these two words – Wait and Hope.

For all evils there are two remedies – time and silence.”

– Edmond Dantès, The Count of Monte Cristo

Somehow, I’d believed that intimacy was rare for me. Family life, friendships, entanglements—all peppered with the same minimal sprinkling of closeness. I say “entanglements,” because at 31, I’ve never had a romantic relationship. I can’t say what that kind of intimacy is . . . or isn’t. Perpetual alone-ness and romantic discontent are not like terms I can combine to mean the same thing.

In mathematics, “combining like terms” is the process of placing constants and their variables with similar ones. For example, 1xy + 3xy, together = 4xy. Unlike terms cannot be combined (4xy, -5y). Math has never been my strong suit; so imagine my surprise when I found out

SOLITUDE ≠ ISOLATION

because my idea of what I was missing was not, in fact, what I was actually missing.

I. Observations

All artwork/Brandy Burgess.

CPR Lesson, 2006. My senior year of high school, all the students in my grade level were given a (non-certified) CPR lesson. During this lesson we were required to observe whether or not the scene was safe and obnoxiously declare, “THE SCENE IS SAFE.” I continued to approach the majority of my life this way (minus the loud declarations), and quarantine was no different.

At first, the scene didn’t seem safe, not with all the toilet paper hawking and the social distancing lines out the door of grocery stores in 40° weather. I opted out completely, but had other troubles. Some of my friends are of an age that placed them in the “most vulnerable” category, and seeing them was out of the question. No more dropping in on my friend to talk about books for hours, no more stopping by to chat with the staff at the cemetery near my house. Outside, the neighbors turned to walking my usual routes, in droves.

There was nowhere to go. Not a single quiet aisle in a grocery store. Living with multiple people meant multiple times less space. There was no place to seek out solitude. It turned out that being trapped in a box with nowhere to go and no one to feel at home in was a recipe for a slow kind of death . . .

II. Problems Without Solutions

Who do we become when we die?

Some of us didn’t die of COVID-19. I thought there might be a name for us, at first. Maybe . . . “the abandoned”? But then I realized we weren’t that—nobody had abandoned us (except maybe ourselves). We were lost, like sailors marooned on an island and condemned to spend the rest of their days in the damning question, what now?

I watched as the scene became safer, became less safe, as people picked up their masks and said “yes,” even as others threw them down and said “no.” I waved at the camera in Zoom, had a social distance picnic, waved across the street to the person I couldn’t hug, had a movie night with my ‘quarantine crew’, waved at the parish priest through the glass window, had a breakdown during the BLM resistance in June, waved away calls about my “safety” and “riots” from concerned white friends, had another breakdown, and fell into a depression.

What now?

Wanting to die is not the same as dying.

Phase I. I could visit the cemetery again, so I did. Masked of course. Six feet, of course.

My friend is the lady in charge. We spoke about the difficulty of burying a loved one and not being present at the funeral. She said, “It’s hard to live without community now, but it’s even harder to die without community.” Who do we become when we die alone?

Death during quarantine meant that you were marooned to passing without your family who would ask, “what now?” Death during quarantine was not an option. But I wanted to die.

To go on living meant responding to the what now? And I couldn’t go on.

But I did go on.

Wanting to die is not the same as dying.

And I went on waking up the morning after that, and the morning after that, and the morning after that…

III. The Sea

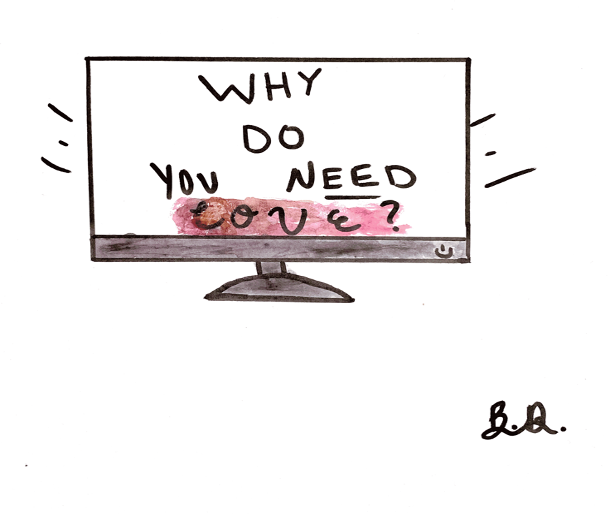

I had a dream about a socially distanced concert on the ocean

We all wore floaties, waves pulling us away from each other

The singer had a voice like Joplin and she wailed “WHY DO YOU NEED LOVE?”

I woke up, in a different bed, in a different home, with the thought still burning: why do you need love?

Eventually, I left the house. Found new routes. Made space in my brain again. Remembered that gratitude multiplies the smallest things and makes the seemingly minimal intimacy more than enough.

Perhaps I confused solitude for emptiness. Maybe the inability to communicate what I need is not the same as being cut off from what I need. Maybe we’re not marooned, just floating in the sea. Perhaps we’re not stuck, just moving in an unknown direction, toward the question, what next?

What is the answer? The answer is the same as the question. They are like terms.